“Hyman, Put Up Your Shutters!” Hyman Levinson and the Eureka Stockade

Posted on: 4 January, 2023Dr Elizabeth Offer

Tales of diggers who became embroiled in the affairs of the Eureka Stockade have been told and retold since its occurrence, yet few, if any, of these stories give voice to the perspective of Jewish migrants present on the Ballarat goldfields. Hyman Levinson, a young Jewish man from Central/Eastern Europe, became entangled in the Eureka Stockade, a tale he told so often to his family and friends that it was later memorialised in his memoirs written by his wife and heavily quoted here1. Born in Prussia in 1834, Hyman Levinson arrived on the Ballarat goldfields in 18542. A watchmaker by trade, Levinson set up a small watch business on the goldfields, selling and repairing watches from his tent. It was while Levinson was at his small tent store that the Eureka Rebellion began, and he became involved in one of colonial Victoria’s most significant events.

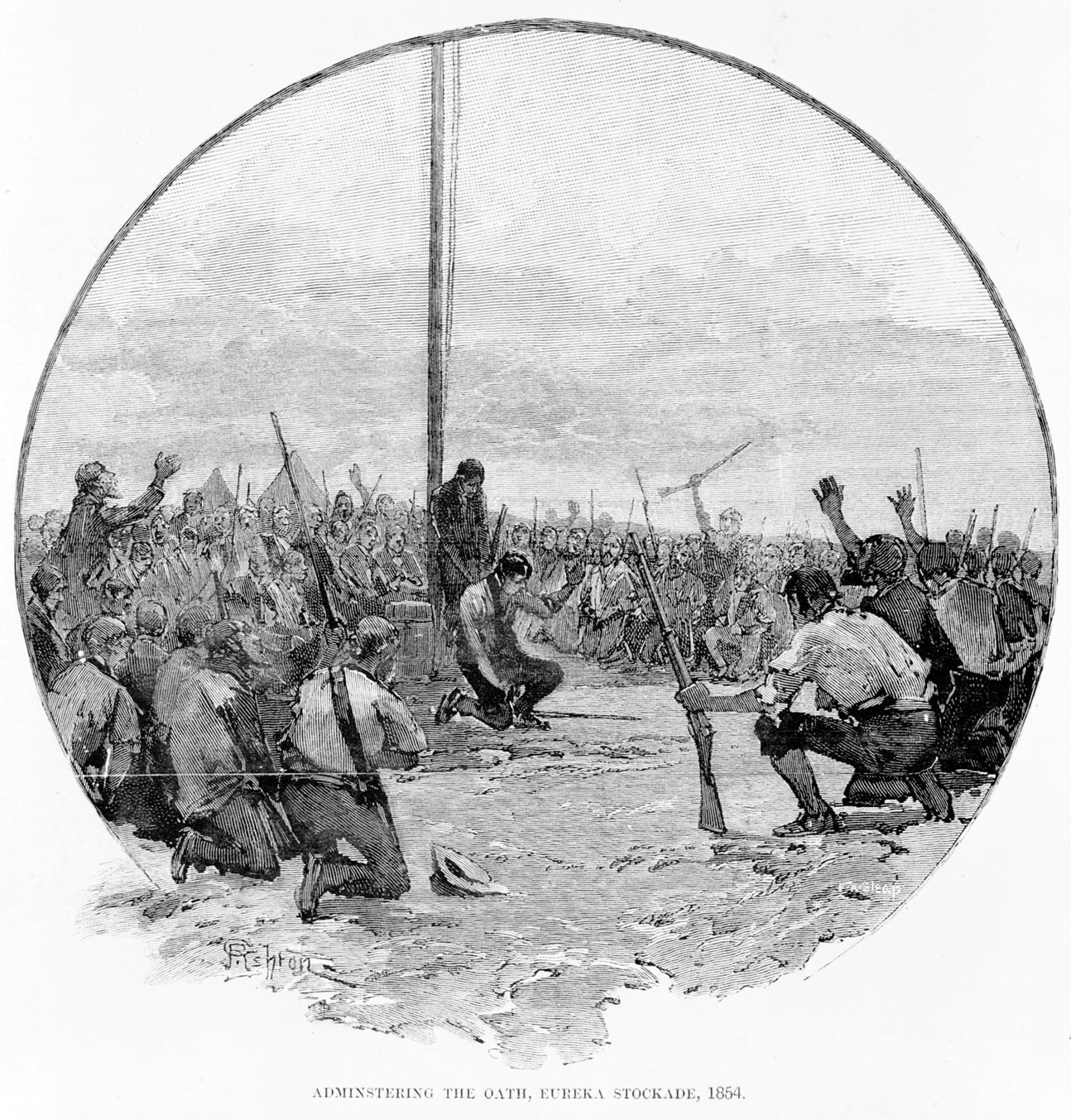

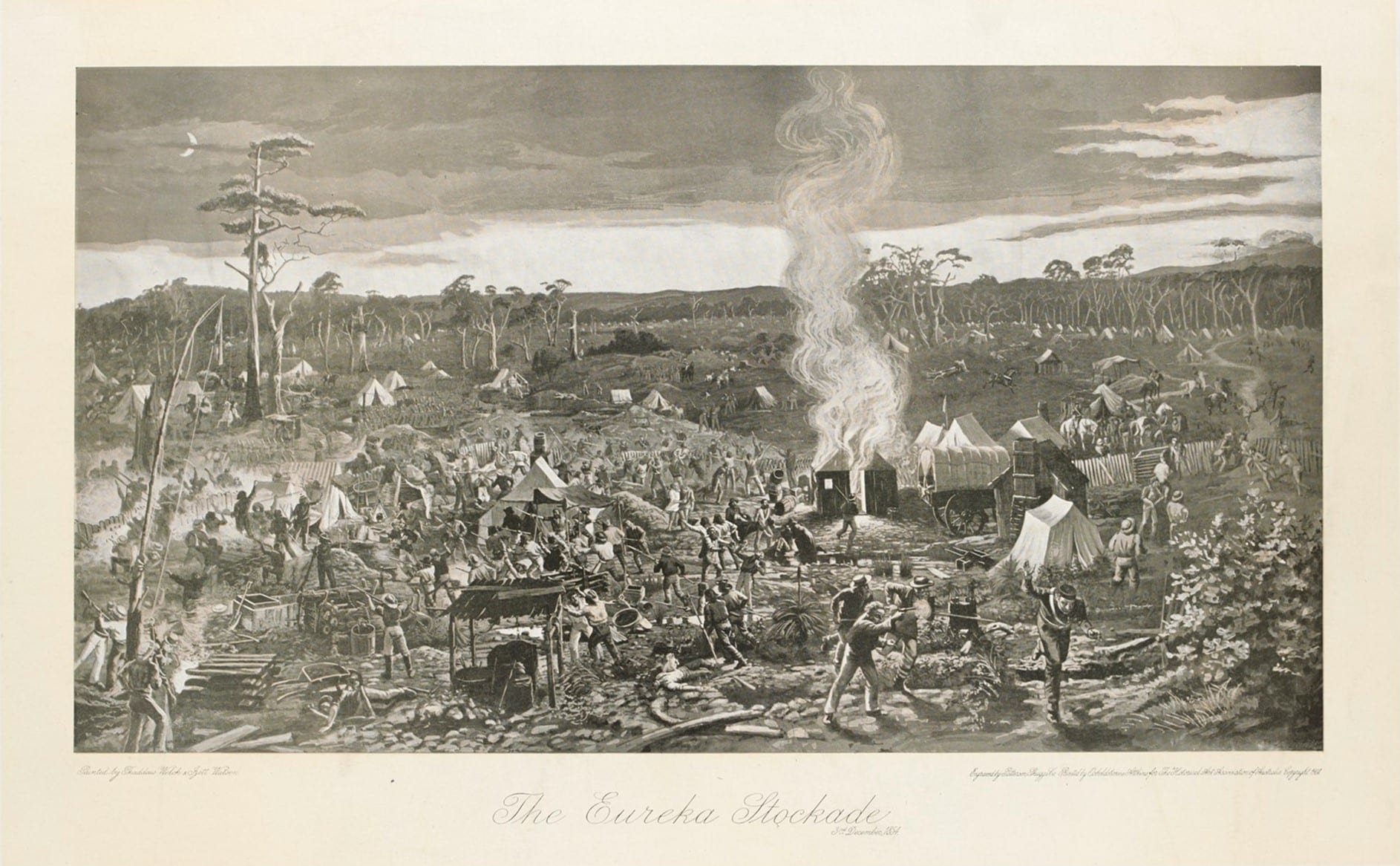

The beginnings of the Eureka conflict dates back to 1853, when ‘monster’ meetings were held for miners to air their complaints regarding police treatment and to set delegates to represent their concerns to the Governor. Angered by the regular license hunts, diggers complained of police extortion, bribery, and unfair imprisonment. Their protests went unheeded, causing further exasperation. When a hotel proprietor was acquitted of murdering a miner late in 1854, the situation quickly escalated as the miners felt there was a miscarriage of justice; the presiding court included a police magistrate who was well-known to have previously accepted bribes from the hotel proprietor on trial3. As tensions grew, a regiment of soldiers was dispatched to the goldfields to reinforce the local police. The Eureka Rebellion occurred in Ballarat in 1854, two months after the above murder trial. The rebellion accumulated in the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, when the miners built a blockade camp and gathered to meet the coming government troops. The stockade lasted for two days, however, the exchange of gunfire was over in only fifteen minutes4. The Eureka Stockade resulted in the known deaths of 35 persons, most of whom were rebel miners. Many more became indirectly involved in the affair as news of the riot quickly spread across the Ballart goldfields, reaching Levinson at his small business.

“Charles Dyte came running along, calling out: “Hyman, put up your shutters!”

“Why?”

“The riot’s begun.”

Arriving on the Ballarat goldfields only a few days previous, Hyman Levinson was cleaning the small window of his business when Charles Dyte, a fellow Jewish migrant, came running by, heralding the beginning of the Eureka Rebellion. Levinson quickly shoved his stock of watches into his trouser pockets and awaited further developments. He watched as a large number of troopers and foot-soldiers, a few hundred by his guess, marched in formation. They soon readied their rifles to shoot, as it seemed to Levinson, right in his direction! As he stood at the door of his tent, a digger came rushing in. Without speaking, the digger took out a revolver. Levinson addressed the man;

“Hullo, mate. What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to shoot that —– fellow,” and he pointed to Captain Wise, in command of the military.

I objected. “There’ll be a volley and we’ll both be shot.”

He persisted. “Well,” I said, “I don’t want to interfere, but I’ll have to go for protection.”

The colloquial language of the goldfields used by Levinson, who was a recent arrival at the time and was likely added later, revealed the attachment he formed to a specific colonial place, to Ballarat. The incorporation of such language as ‘mate’ by Levinson and the reference to key persons like Captain Wise speaks to the deeper importance placed on stories, identities, and goldfields histories. In this story, future identifications merge with past events, layering the narrative with understandings of both continuity and change. At this moment in the story, however, the comradery usually born of a shared language did little to improve Levinson’s situation.

With his protests disregarded, Levinson called out to the troopers. Captain Wise himself rode up to Levinson’s tent to inquire what was the matter, but the digger had fled. The captain rode away, and Levinson was left at his tent to wait and watch the coming events. A short while later, a group of men approached Levinson with the digger who barged into his tent at the head, pointing and exclaiming ‘that’s the fellow!’ The diggers demanded to know why Levinson had called the troopers.

“I tried to explain, but it was useless. They were all Germans. They attacked me. I was struck again and again. My window was smashed; my tent pulled down. I ran and they pursued me.”

As Levinson ran, he stopped at the stores of friends and acquaintances, however, fearing for their own safety, they refused to let him in, further fuelling Levinson’s own fright. The German identity of the pursuing diggers may have recalled for Levinson the prejudice he had experienced in Prussia where Jewish communities were at the time suffering under restricted movement and targeted discrimination. Coming across his friend Samuels, a German speaker, the diggers were temporarily waylaid, giving Levinson time to escape. Eventually, Levinson came cross the tent of a Manchester friend and was given refuge in a store. Levinson hid for three days as the diggers searched for him, who swore that they would kill Levinson if he was found. On the third day, Levinson and his friend heard the commotion of the Eureka Stockade. They both witnessed the horrible aftermath of the conflict with diggers laying wounded or dead and tents burnt down. The Eureka Rebellion was over.

Afterwards, Levinson visited the Goldfields Commissioner to provide information on the diggers who robbed and assaulted him, although he did not provide names.

“Then I sent word to the principal offender that, if he did not molest me, I would not tell on him, but I would at once if he or his fellows troubled me. Afterwards they were among my best customers.”