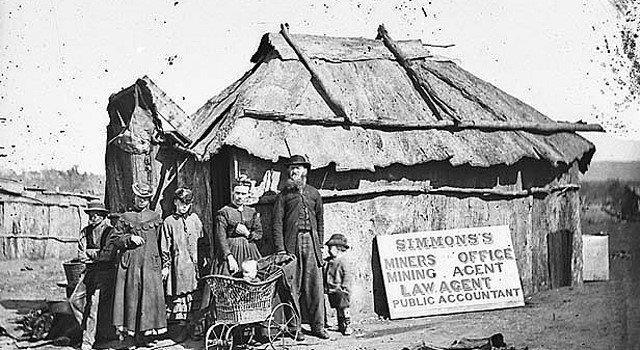

During the early 1850s, there weren’t many women on the Victorian goldfields, due to the harsh conditions and the many social impediments they faced. However, by 1854, Ballarat had a population of nearly 35% women – about 10% higher than was typical across the Australian colonies. With people flooding into the colonies in search of gold, some women chose to accompany their husbands or brothers, not just for domestic duties but to also work on the diggings alongside their menfolk. Although living in a tent was rough, the men did try to take account of the women by portioning off part of the tent where the women could sleep and maintain privacy.

Many women accompanied brothers, fathers and husbands to the goldfields. As well as doing the domestic chores that were required, some women worked on the goldfields as well. Often it was to help the male member/s of the party who may have been taken ill or have been injured, to continue to work the claim. But on rare occasions some decided to work beside their husbands or brothers and look for gold. There are records of women dressing as men as the goldfields were not seen as a place for women to work.

Ellen Clacy’s 'A Lady’s’ visit to the Gold Diggings of Australia' is an important resource concerning the experiences of immigrant women in colonial Victoria. Her account of life on the goldfields is fascinating for the way in which she details the challenges faced by women who arrived with their families. The book can be read online using this link: Click here.

One of the most intriguing stories she tells is that of a woman named Harriette Walters. After her husband experienced financial troubles in England, he and Harriette decided to emigrate to Victoria. Her husband left three weeks prior, but Harriette’s ship was ‘a fast sailer, the winds were favourable…’ and she arrived first and waited three weeks for her husband’s arrival. Ellen writes:

“Alone and unprotected in that strange, rough city, without money, without friends, she felt truly wretched. It was not a place for a female to be without a protector, and she knew it…She possessed little money, lodgings and food were at an awful price, and employment for a female, except of a rough sort, was not easily procured.

In this dilemma she took the singular notion into her head of disguising her sex, thereby avoiding much of the insult and annoyance to which an unprotected female would have bee liable…Harriette passed very well for what she assumed to be – a young lad just arrived from England. She immediately obtained a light situation near the wharf, where for about three weeks she worked hard enough at a salary of a pound a week, board, and permission to sleep in an old tumbledown shed beside the store.

At last the long looked-for vessel arrived. That must have been a moment of intense happiness which restored her to her husband’s arms – for him not unmingled with surprise; he could not at first recognize her in her new garb. She would hear of no further separation, and when she learnt he had joined a party for the Bendigo diggings, she positively refused to remain in Melbourne, and she retained her boyish dress until the arrival in Bendigo...”

Simon Jacks

Australiana Research Collection

Ballarat Research Hub at Eureka (BRHAE)

![Bush scene, three women panning for gold [location unknown] c.1855-1910 State Library Victoria, H81.23/9.](/sites/default/files/styles/responsive_image_1200/public/media/image/H81%20239.jpg?itok=9Gchr3Ok)